Smoking Increases Childhood Language Disorder Severity

Introduction

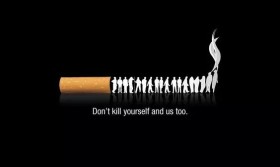

Childhood language disorders (CLDs) are developmental conditions that affect a child’s ability to understand, process, and produce language. These disorders can lead to long-term academic, social, and emotional challenges. While genetic and neurological factors play a significant role in CLDs, environmental influences—such as prenatal and postnatal exposure to tobacco smoke—have increasingly been linked to worsened language disorder severity. Research indicates that maternal smoking during pregnancy and secondhand smoke exposure in early childhood can impair cognitive and linguistic development, exacerbating existing language impairments. This article explores the mechanisms by which smoking contributes to CLDs, reviews relevant studies, and discusses potential interventions to mitigate these risks.

The Link Between Smoking and Language Development

1. Prenatal Exposure to Tobacco Smoke

Maternal smoking during pregnancy introduces harmful chemicals—such as nicotine, carbon monoxide, and heavy metals—into the fetal bloodstream. These toxins interfere with brain development, particularly in regions responsible for language processing (e.g., Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas). Studies have shown that:

- Nicotine disrupts neurotransmitter activity, impairing synaptic plasticity crucial for language acquisition.

- Reduced oxygen supply due to carbon monoxide exposure can lead to developmental delays.

- Altered gene expression in the fetus may increase susceptibility to neurodevelopmental disorders.

A 2020 study published in Pediatrics found that children exposed to prenatal smoking were 30% more likely to exhibit severe language delays compared to unexposed peers.

2. Postnatal Secondhand Smoke Exposure

Even after birth, children exposed to secondhand smoke (SHS) face heightened risks. SHS contains over 7,000 chemicals, many of which are neurotoxic. Key findings include:

- Impaired auditory processing, which is essential for language comprehension.

- Increased risk of middle ear infections, leading to temporary hearing loss and speech delays.

- Oxidative stress and inflammation, damaging neural pathways involved in language development.

A longitudinal study in JAMA Pediatrics (2019) reported that children exposed to SHS before age 5 had poorer vocabulary and grammar skills than those in smoke-free environments.

Biological Mechanisms Behind the Damage

1. Neurotoxicity of Tobacco Byproducts

Nicotine binds to acetylcholine receptors in the fetal brain, disrupting normal neuronal migration and differentiation. This can result in:

- Reduced gray matter volume in language-related brain regions.

- Slower myelination, affecting neural signal transmission.

2. Epigenetic Modifications

Tobacco smoke can alter DNA methylation patterns, silencing genes that regulate neurodevelopment. These changes may persist into childhood, increasing vulnerability to language disorders.

3. Inflammatory Responses

Chronic exposure to smoke triggers systemic inflammation, which has been linked to neurodevelopmental impairments, including:

- Dysregulated synaptic pruning, leading to inefficient neural networks.

- Increased risk of ADHD and autism spectrum disorders, which often co-occur with language delays.

Case Studies and Research Evidence

1. The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)

This UK-based study tracked 14,000 children from birth to adolescence. Findings revealed that:

- Children whose mothers smoked during pregnancy had lower verbal IQ scores at age 8.

- Postnatal smoke exposure was associated with reduced reading comprehension abilities.

2. The Danish National Birth Cohort Study

Analyzing over 100,000 pregnancies, researchers found:

- A dose-dependent relationship between maternal smoking and language delays.

- Heavy smokers (>10 cigarettes/day) had children with twice the risk of severe language impairment.

Mitigating the Risks: Prevention and Intervention

1. Smoking Cessation Programs for Expectant Mothers

Public health initiatives should prioritize:

- Free nicotine replacement therapies for pregnant women.

- Behavioral counseling to reduce relapse rates.

2. Policy Measures to Reduce Secondhand Smoke Exposure

- Stricter smoking bans in homes and public spaces.

- Educational campaigns highlighting the cognitive risks of SHS.

3. Early Screening and Speech Therapy

Children with smoke exposure histories should receive:

- Regular developmental assessments to detect language delays early.

- Targeted speech-language pathology interventions to improve outcomes.

Conclusion

The evidence is clear: smoking—whether prenatal or postnatal—significantly exacerbates childhood language disorder severity. By damaging developing brains through neurotoxic, epigenetic, and inflammatory pathways, tobacco smoke creates lasting linguistic deficits. Addressing this issue requires multi-level interventions, from smoking cessation support to early therapeutic interventions for affected children. Reducing tobacco exposure must be a public health priority to safeguard children’s cognitive and linguistic futures.

Tags: #ChildDevelopment #LanguageDisorders #SmokingEffects #Neurodevelopment #PublicHealth