Title: Tobacco Smoke Exposure: A Critical Driver of Pediatric Asthma Readmission

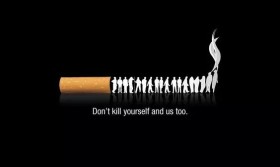

Pediatric asthma remains one of the most prevalent chronic conditions affecting children worldwide, representing a significant source of morbidity, healthcare utilization, and familial stress. While emergency department visits and initial hospitalizations are critical events, a more telling metric of both disease management failure and healthcare system burden is the hospital readmission rate. A myriad of factors influences this rate, from medication adherence and socioeconomic status to access to outpatient care. However, a pervasive and potent environmental correlate consistently emerges from the data: exposure to tobacco smoke. This article delves into the robust epidemiological evidence, the pathophysiological mechanisms, and the critical clinical and public health implications of the link between tobacco smoke and pediatric asthma readmissions.

The Unavoidable Data: Epidemiology of Smoke and Readmission

Numerous large-scale cohort studies and retrospective analyses have established an undeniable correlation between tobacco smoke exposure (TSE) and an increased risk of asthma readmission in children. This exposure is typically categorized as either pre-natal (maternal smoking during pregnancy) or post-natal (secondhand or thirdhand smoke in the child's environment).

Pre-natal exposure is particularly insidious. Studies show that children born to mothers who smoked during pregnancy have a higher likelihood of developing asthma and, crucially, experience more severe and persistent forms of the disease. This is often attributed to in-utero alterations in lung development and immune function. These children present with smaller airways and heightened immune responsiveness, creating a physiological predisposition for severe exacerbations that necessitate hospitalization. Consequently, they form a high-risk group for repeated admissions.

Post-natal secondhand smoke exposure acts as a continuous trigger and irritant. Research demonstrates that children with asthma living in households with smokers have a significantly higher risk of readmission within 30, 90, and 180 days of an initial hospitalization compared to those in smoke-free homes. The dose-response relationship is clear: the number of smokers in the home and the quantity of cigarettes smoked indoors directly correlate with the frequency and severity of asthma attacks. Thirdhand smoke—the toxic residue that clings to surfaces, dust, and fabrics long after a cigarette has been extinguished—presents a further, often underestimated, risk, especially for crawling infants and toddlers who have intense hand-to-mouth contact.

The Pathophysiological Pathway: How Smoke Drives Disease

Understanding why tobacco smoke is such a powerful driver of readmission requires an examination of its multifaceted assault on a child's respiratory system.

-

Airway Inflammation and Hyperresponsiveness: Tobacco smoke is a complex mixture of over 7,000 chemicals, hundreds of which are toxic. These substances, including nicotine, carbon monoxide, and fine particulate matter, are potent irritants. Upon inhalation, they trigger a robust inflammatory response in the bronchial airways. This involves the recruitment of neutrophils and other inflammatory cells, leading to edema (swelling), increased mucus production, and smooth muscle constriction. In an asthmatic child whose airways are already chronically inflamed and hyperresponsive, this additional insult dramatically lowers the threshold for a severe bronchospasm, culminating in an acute exacerbation requiring emergency care.

-

Impaired Mucociliary Clearance: The respiratory tract is lined with cilia—tiny hair-like structures that rhythmically beat to move mucus and trapped pathogens out of the lungs. Tar and other components of tobacco smoke paralyze and destroy these cilia. This cripples the lung's primary defense mechanism, allowing allergens, viruses, and irritants to remain in contact with the airway lining for longer periods, perpetuating inflammation and increasing the risk of secondary infections, which are common precursors to asthma attacks.

-

Altered Immune Response: Exposure to tobacco smoke dysregulates the immune system. It can skew responses toward a T-helper type 2 (Th2) dominant phenotype, which is central to allergic asthma pathways, amplifying the reaction to common allergens like dust mites or pet dander. Simultaneously, it can impair the innate immune response to common respiratory viruses like Rhinovirus (the common cold virus), which is the leading trigger of severe asthma exacerbations in children. A child exposed to smoke is therefore both more likely to get sick and more likely to have that illness trigger a catastrophic asthma attack.

-

Reduced Efficacy of Corticosteroids: Perhaps one of the most concerning mechanisms is evidence that tobacco smoke may induce relative corticosteroid resistance. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the mainstay of preventive asthma management. Exposure to oxidative stress from smoke can alter molecular pathways within lung cells, making them less responsive to the anti-inflammatory effects of ICS. This means that even a child on seemingly appropriate controller therapy may have uncontrolled underlying inflammation if they are consistently exposed to smoke, rendering their preventive medication less effective and leaving them vulnerable to exacerbations.

Beyond Biology: The intertwined Social Determinants

The correlation between TSE and asthma readmission is not solely biological; it is deeply entangled with social determinants of health. Smoking rates are disproportionately higher among populations facing economic hardship, lower educational attainment, and limited access to healthcare. These same populations often experience other barriers to optimal asthma control, including:

- Suboptimal medication adherence due to cost or complexity.

- Poor housing quality with increased exposure to other triggers like mold, cockroaches, and dust mites.

- Limited access to consistent primary care and asthma specialists.

- Food insecurity and stress, which can also worsen asthma outcomes.

Therefore, tobacco exposure often serves as a marker for a broader constellation of social and economic challenges that compound a child's risk. A readmission is frequently the result of this toxic synergy between a harmful environmental exposure and systemic inequities.

Clinical and Public Health Imperatives

This compelling evidence base translates into clear imperatives for action at multiple levels.

In the Clinical Setting:

- Universal Screening: Every child admitted for asthma must be systematically screened for tobacco smoke exposure. This involves asking non-judgmental, specific questions about smoking in the home and car.

- Smoking Cessation Intervention: The hospitalization of a child is a "teachable moment" and a powerful incentive for parents and caregivers to quit smoking. Healthcare systems must integrate evidence-based cessation support into pediatric care pathways. This includes providing counseling, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) referrals, and follow-up support. Framing cessation as a critical medical treatment for their child's illness is far more effective than simply telling a parent to quit.

- Education on Thirdhand Smoke: Counseling should extend to the dangers of thirdhand smoke and practical advice on reducing exposure, such as implementing strict smoking bans indoors and in cars, and washing hands and changing clothes after smoking before contact with the child.

In the Public Health Arena:

- Policy Interventions: Strengthening and enforcing smoke-free laws in multi-unit housing, cars with children present, and public spaces can drastically reduce community-level exposure.

- Targeted Cessation Programs: Developing and funding cessation programs specifically aimed at parents and caregivers of children with asthma.

- Continued Research: Supporting research into interventions that effectively reduce TSE in pediatric populations and studying the long-term impact of such interventions on readmission rates and overall child health.

Conclusion

The correlation between tobacco smoke exposure and pediatric asthma readmission rates is strong, consistent, and biologically plausible. It represents a modifiable risk factor in a often complex and frustrating clinical scenario. While managing asthma requires a multi-pronged approach addressing medications, allergies, and social needs, mitigating tobacco exposure is arguably one of the most impactful single interventions available. By systematically addressing this environmental trigger through vigilant clinical screening, supportive cessation programs, and robust public health policies, healthcare providers and communities can break this cycle, leading to fewer hospital readmissions, better-controlled asthma, and healthier lives for children.

Tags: #PediatricAsthma #AsthmaReadmission #TobaccoSmokeExposure #SecondhandSmoke #ThirdhandSmoke #HealthDisparities #PublicHealth #AsthmaTriggers #RespiratoryHealth #PreventiveCare