Title: The Unseen Toll: How Smoking Exacerbates Skin Hypopigmentation

The detrimental effects of smoking on human health are widely documented, ranging from cardiovascular diseases to respiratory disorders and various forms of cancer. However, a less discussed yet significant consequence of tobacco use is its impact on skin health, particularly its role in accelerating skin aging and disrupting pigmentation. Emerging evidence suggests that smoking is a potent environmental factor that can enlarge hypopigmented spot areas on the skin, a condition characterized by patches of skin losing their natural color. This phenomenon is not merely a cosmetic concern but a reflection of underlying cellular damage and systemic inflammation induced by the myriad toxic compounds in cigarette smoke.

Understanding Skin Hypopigmentation Hypopigmentation refers to the loss of skin color due to a reduction in melanin production or the absence of melanocytes, the cells responsible for pigment synthesis. Common conditions include vitiligo, post-inflammatory hypopigmentation, and idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. These spots appear lighter than the surrounding skin and can vary in size and distribution. While genetics play a crucial role in such conditions, environmental triggers like UV exposure, chemical exposure, and lifestyle factors such as smoking can exacerbate their progression and severity.

The Chemical Assault on Skin Physiology Cigarette smoke contains over 7,000 chemicals, including nicotine, carbon monoxide, tar, and numerous free radicals. These compounds inflict damage through multiple pathways. Nicotine, for instance, causes vasoconstriction, reducing blood flow to the skin. This impairs the delivery of oxygen and essential nutrients while hindering the removal of toxic waste products. The resulting hypoxia and nutrient deficiency compromise skin cell viability, including melanocytes. Over time, this can lead to melanocyte apoptosis (cell death) or dysfunction, reducing melanin synthesis in affected areas and enlarging existing hypopigmented spots.

Moreover, free radicals in smoke generate oxidative stress, a key driver of skin damage. Oxidative stress overwhelms the skin's antioxidant defenses, leading to lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, and DNA mutation. Melanocytes are particularly susceptible to oxidative damage due to their high metabolic activity and the inherent pro-oxidant nature of melanin synthesis. This can trigger an autoimmune response where the body attacks its own melanocytes, a mechanism similar to that observed in vitiligo. Studies have shown that smokers have higher levels of inflammatory markers like TNF-α and interleukin-6, which are implicated in melanocyte destruction and hypopigmentation disorders.

Disruption of Melanogenic Pathways Melanin production is a complex process regulated by enzymes, hormones, and signaling pathways. Smoking interferes with this process in several ways. Carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin with a higher affinity than oxygen, creating functional anemia and further starving cells of oxygen. Hypoxia inhibits the activity of tyrosinase, the key enzyme in melanin synthesis, thereby reducing pigment production. Additionally, nicotine has been shown to alter calcium signaling and downregulate melanogenic genes, directly impairing melanocyte function.

The endocrine-disrupting chemicals in tobacco smoke also play a role. Smoking affects cortisol levels, increasing systemic stress, which is known to worsen autoimmune conditions like vitiligo. It also alters estrogen metabolism; estrogen is known to influence melanin production, and its disruption can lead to irregular pigmentation.

Synergy with Other Risk Factors Smoking often synergizes with other risk factors, amplifying skin damage. For example, many smokers have concurrent habits like excessive sun exposure or poor nutrition. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is a known trigger for hypopigmentation in susceptible individuals, and smoking compounds this effect by depleting skin antioxidants like vitamin C and E, which are crucial for protecting against UV-induced damage. The combined insult of UV radiation and smoke-derived toxins accelerates melanocyte apoptosis, leading to more extensive and larger hypopigmented areas.

Furthermore, smoking accelerates skin aging through the degradation of collagen and elastin via increased matrix metalloproteinase activity. Aged skin is more prone to pigmentation disorders due to a reduced number and function of melanocytes. Thus, the premature aging induced by smoking creates a conducive environment for hypopigmentation to develop and spread.

Clinical Evidence and Observations Epidemiological studies support the link between smoking and hypopigmentation. Research on vitiligo patients has shown that smokers often have a more severe and rapidly progressing form of the disease compared to non-smokers. A study published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology found that smokers had a higher prevalence of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, with lesions appearing larger and more numerous. Another investigation noted that smokers with post-inflammatory hypopigmentation experienced slower repigmentation and poorer response to treatment, suggesting that smoking impedes the skin's natural healing and regenerative processes.

Implications for Treatment and Prevention The role of smoking in enlarging hypopigmented spots has significant clinical implications. Dermatologists often emphasize smoking cessation as a critical component of managing pigmentation disorders. Quitting smoking can halt the progression of hypopigmentation by restoring blood flow, reducing oxidative stress, and allowing the skin's repair mechanisms to function optimally. Antioxidant supplements and topical treatments may be more effective in non-smokers or after cessation, as they are no longer combating the constant influx of free radicals from tobacco smoke.

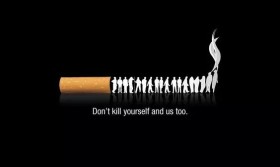

Preventively, public health messages should highlight the dermatological consequences of smoking, including hypopigmentation, to motivate individuals to avoid or quit smoking. Unlike lung cancer or heart disease, skin changes are visible and often cause psychological distress, which can be a powerful incentive for behavior change.

Conclusion Smoking is a modifiable risk factor that significantly contributes to the enlargement of hypopigmented skin spots through mechanisms involving vasoconstriction, oxidative stress, inflammation, and disruption of melanogenic pathways. Its synergy with other environmental insults exacerbates the damage, leading to more pronounced and widespread pigmentation loss. Recognizing this connection is vital for both clinical management and prevention strategies. As research continues to unravel the complex interplay between tobacco smoke and skin biology, it becomes increasingly clear that preserving skin health requires not only topical care but also a commitment to a smoke-free lifestyle.