The Economic Burden of Smoking: How Tobacco Use Inflates Community-Acquired Pneumonia Treatment Costs

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) remains a formidable public health challenge, representing a leading cause of hospitalization and mortality worldwide. While the clinical ramifications of smoking on respiratory health are well-documented, a less explored but critically important dimension is the profound economic impact. A growing body of evidence conclusively demonstrates that smoking significantly escalates the direct and indirect costs associated with treating CAP, placing an immense, preventable strain on healthcare systems, insurers, and patients themselves. This financial burden is not merely a reflection of higher hospitalization rates but is woven into every stage of the disease process, from pathogenesis and diagnosis to treatment and long-term recovery.

The Pathophysiological Link: A Recipe for Complicated and Costly Care

To understand the cost implications, one must first appreciate the biological havoc smoking wreaks on the lungs' defense mechanisms. Tobacco smoke contains over 7,000 chemicals, which collectively impair ciliary function—the tiny hair-like structures that sweep mucus and pathogens out of the airways. It also disrupts the integrity of the epithelial barrier and suppresses the activity of alveolar macrophages, the lungs' primary immune sentinels. This trifecta of damage creates an environment where pathogens, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Legionella pneumophila, can easily colonize and invade.

For a patient with CAP, these pre-existing vulnerabilities translate into a more severe and complicated clinical presentation. Smokers are more likely to present with advanced disease, higher severity scores (e.g., CURB-65 or PSI), and a greater risk of developing parapneumonic effusions, empyema, lung abscesses, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). This directly dictates a more intensive and expensive treatment pathway. Where a non-smoking, otherwise healthy individual might be managed with oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis, a smoker often requires immediate hospitalization.

Dissecting the Cost Drivers: From Admission to Discharge

The inflation of treatment costs for smokers with CAP is multi-faceted, impacting numerous line items within a healthcare budget.

Increased Hospitalization Rates and Length of Stay (LOS): This is the most significant cost driver. Smokers are hospitalized for CAP at a substantially higher rate than non-smokers. Once admitted, their average length of stay is prolonged. The need for more time to achieve clinical stability, resolve fever, and normalize white blood cell counts extends their time in an acute care bed, which is among the most expensive components of healthcare. Each additional day in the hospital adds thousands of dollars to the total bill, covering room charges, nursing care, and administrative overhead.

Demand for Intensive Care and Advanced Support: The propensity for severe complications means smokers disproportionately require admission to Intensive Care Units (ICUs). ICU care is exponentially more costly than general ward care due to the need for continuous monitoring, specialized nursing, and advanced life support equipment. The need for invasive mechanical ventilation—a common consequence of respiratory failure in severe pneumonia—is a major cost multiplier. The procedure itself, the sedation required, and the associated risks (like ventilator-associated pneumonia) create a cascade of expensive interventions.

Complex Diagnostic Workload: The smoker's lung is often already damaged, presenting a complex diagnostic picture. Radiological findings can be obscured by pre-existing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema. Distinguishing a pneumonia infiltrate from other pathologies may require more frequent chest X-rays or computed tomography (CT) scans. Furthermore, the higher risk of complications like empyema necessitates diagnostic thoracocentesis and ultrasound or CT guidance, each adding to the diagnostic cost burden.

Broad-Spectrum and Prolonged Antimicrobial Therapy: Due to their immunocompromised state and the risk of infection with more virulent or atypical pathogens, smokers often require broader-spectrum empiric antibiotic therapy. These second-line or third-line antibiotics are far more expensive than first-line agents like amoxicillin. Treatment failure and the need to switch antibiotics are also more common, leading to duplicate pharmacy costs. The duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy is often longer, requiring more resources for administration and monitoring.

Higher Rates of Readmission and Long-Term Morbidity: The episode of care does not end at discharge. Smokers recovering from CAP have poorer long-term outcomes. They are at a higher risk of readmission within 30 days, often due to recurrent infection or exacerbation of underlying smoking-related lung disease. This triggers additional costs for the healthcare system under value-based care models that penalize avoidable readmissions. Furthermore, the recovery process is slower, leading to greater indirect costs from lost productivity and extended absenteeism from work.

The Ripple Effect: Systemic and Societal Costs

The financial impact extends beyond the hospital's walls. Health insurance premiums rise for everyone as insurers adjust to the higher claims associated with treating smoking-related illnesses. Employers bear the cost of increased sick leave and reduced productivity. For patients and their families, the financial toxicity includes not only higher out-of-pocket medical expenses but also lost wages, creating a cycle of economic hardship that impedes recovery.

Public health systems, already operating under constrained budgets, are forced to allocate a disproportionate share of resources to manage a preventable condition. The money spent on treating smoking-aggravated CAP could be redirected to preventive care, vaccination programs, or other essential health services, representing a significant opportunity cost for the entire community.

Conclusion: A Compelling Economic Argument for Prevention

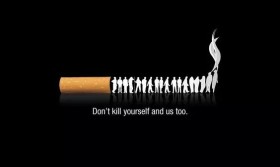

The evidence is clear: a history of smoking is a powerful predictor of increased CAP treatment costs. It transforms a potentially straightforward infection into a protracted, complex, and expensive medical ordeal. This economic analysis provides a powerful, complementary argument to the well-known health incentives for smoking cessation. Investing in robust tobacco control programs—including public education, cessation support services, and regulatory measures—is not just a public health imperative but a sound financial strategy. Reducing smoking rates would directly translate into a substantial decrease in the economic burden of CAP, freeing up vital resources and creating a healthier, more economically resilient community. Ultimately, every dollar spent on preventing smoking is an investment that yields returns through avoided healthcare costs, demonstrating that what is good for the lungs is also good for the ledger.