Title: The Detrimental Impact of Smoking on Nebulization Efficacy in Pediatric Recurrent Wheezing

Introduction

Pediatric recurrent wheezing is a common clinical challenge, affecting a significant portion of children worldwide. It is characterized by high-pitched whistling sounds during breathing, often indicative of underlying airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. A cornerstone of managing acute episodes is nebulized medication, particularly bronchodilators like albuterol and corticosteroids, which deliver therapeutic agents directly to the lungs to relieve bronchoconstriction and reduce inflammation. However, clinical efficacy can vary dramatically among patients. A critical, and often modifiable, factor undermining this vital treatment is exposure to tobacco smoke. This article explores the compelling evidence that secondhand and thirdhand smoke exposure significantly reduces the efficacy of nebulization therapy in children with recurrent wheezing, delving into the pathophysiological mechanisms and emphasizing the urgent need for comprehensive environmental interventions.

Understanding Pediatric Recurrent Wheezing and Nebulization

Recurrent wheezing in children is not a single disease but a symptom complex associated with various conditions, including asthma, viral-induced wheeze, and bronchiolitis. The common denominator is airway inflammation, mucosal edema, and bronchial smooth muscle constriction, leading to narrowed airways and difficult breathing. Nebulization therapy is highly effective because it converts liquid medication into a fine mist, allowing for deep penetration into the lower respiratory tract. This provides rapid localized action with minimal systemic side effects, making it the gold standard for acute relief. The expected outcome is swift bronchodilation, reduced work of breathing, and resolution of wheezing. When this expected relief is blunted or absent, it constitutes a treatment failure, placing the child at risk for emergency department visits, hospitalization, and prolonged suffering.

The Insidious Role of Tobacco Smoke: Beyond a Mere Trigger

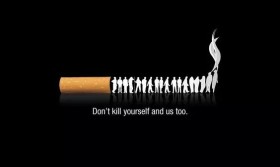

It is well-established that tobacco smoke is a potent trigger for wheezing episodes. It contains over 7,000 chemicals, hundreds of which are toxic and about 70 known to cause cancer. For a child with sensitive airways, exposure acts as a direct irritant, provoking inflammation and bronchoconstriction. However, its role is far more sinister than just being a trigger; it actively compromises the body's ability to respond to rescue medication.

The primary routes of exposure are:

- Secondhand Smoke (SHS): The involuntary inhalation of smoke from burning tobacco products (sidestream smoke) and smoke exhaled by a smoker (mainstream smoke).

- Thirdhand Smoke (THS): The residual nicotine and chemicals left on surfaces like clothing, hair, furniture, and car interiors long after a cigarette has been extinguished. These residues can form toxic compounds that are ingested, inhaled, or absorbed through the skin, posing a particular danger to crawling infants and toddlers.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms: How Smoke Undermines Treatment

The reduction in nebulization efficacy is not a simple correlation but a consequence of specific, smoke-induced pathological changes in the respiratory system.

-

Altered Airway Architecture and Inflammation: Chronic exposure to tobacco smoke leads to persistent airway inflammation, characterized by an influx of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and other inflammatory cells. This creates a thickened airway wall due to edema and remodeling. The physical barrier of inflamed and swollen mucosa impedes the delivered nebulized medication from reaching its target receptors on the smooth muscle cells deep within the airways. Essentially, the drug cannot penetrate effectively to where it is needed most.

-

Receptor Downregulation and Desensitization: Nebulized bronchodilators like albuterol work by binding to beta-2 adrenergic receptors on airway smooth muscle, causing relaxation and dilation. Chronic smoke exposure has been shown to downregulate these receptors, meaning there are fewer available for the medication to bind to. Furthermore, smoke can cause receptor desensitization, a phenomenon where the receptor becomes less responsive to stimulation even if the drug successfully binds. This directly translates to a diminished bronchodilator response.

-

Increased Mucus Production and Altered Clearance: Tobacco smoke stimulates goblet cells to produce excessive, thick mucus. This viscous mucus plugs the airways, physically blocking the path of the nebulized aerosol. The cilia, tiny hair-like structures responsible for clearing mucus and debris from the airways, are paralyzed and damaged by smoke toxins. This impaired mucociliary clearance means that even if medication is delivered, the resulting loosened secretions cannot be effectively cleared, perpetuating airway obstruction.

-

Oxidative Stress and Pharmacological Interference: The multitude of free radicals and oxidants in tobacco smoke creates a state of high oxidative stress in the lungs. This environment can directly inactivate certain medications or interfere with their pharmacological pathways. The oxidative stress also contributes to heightened bronchial hyperresponsiveness, creating a state where the airways are constantly on the verge of constriction, making them harder to treat with standard doses.

Clinical Evidence and Implications

Numerous studies support this concerning interaction. Research consistently shows that children with asthma or recurrent wheezing who are exposed to tobacco smoke have:

- Poorer overall symptom control.

- Increased frequency and severity of exacerbations.

- Higher rates of emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

- A significantly blunted response to inhaled bronchodilators during acute episodes.

For the clinician at the bedside, this manifests as a child who requires more frequent nebulization treatments, higher doses of medication, longer hospital stays, and a greater need for systemic corticosteroids to achieve the same level of relief that an unexposed child would achieve with standard therapy. This not only increases healthcare costs but also exposes the child to potential side effects from escalated treatment.

Conclusion and Call to Action

The evidence is clear: tobacco smoke exposure is a major contributor to treatment-resistant wheezing in children. It actively sabotages the mechanism of action of nebulized therapies through inflammation, architectural changes, receptor dysfunction, and mucus plugging. Therefore, administering nebulized medication to a child in a smoke-free environment is fundamentally different from administering it to a child continually exposed to smoke toxins.

Addressing this issue requires moving beyond simply prescribing medication. Healthcare providers must:

- Routinely Screen: Systematically ask about smoke exposure in every household of a wheezing child.

- Provide Unequivocal Counseling: Clearly and emphatically explain to parents and caregivers that smoking is directly reducing the effectiveness of their child's medicine, prolonging their illness, and increasing their risk of hospitalization.

- Promote Cessation Support: Provide resources, referrals to smoking cessation programs, and encourage strict smoke-free home and car policies. Emphasizing the immediate health benefit for their child can be a powerful motivator for cessation.

Ultimately, achieving optimal control of pediatric recurrent wheezing depends not only on the medication in the nebulizer cup but also on the quality of the air the child breathes at home. A comprehensive treatment plan must include a vigorous assault on tobacco smoke exposure to ensure that life-saving nebulization therapies can work as intended.