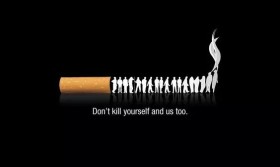

Title: The Unseen Toll: How Smoking Depletes Skin Elastic Fiber Density and Accelerates Aging

The detrimental health effects of smoking, particularly its association with lung cancer, heart disease, and respiratory conditions, are widely publicized and recognized. However, a more insidious and visibly apparent consequence often remains in the shadows: its profound and destructive impact on skin health. Beyond the well-known surface-level issues like wrinkles and a sallow complexion lies a deeper, biological assault on the skin's fundamental architecture. A growing body of scientific evidence conclusively demonstrates that smoking significantly reduces skin elastic fiber density, a key structural component responsible for skin's resilience, firmness, and youthful appearance. This process effectively accelerates intrinsic aging, leading to premature and often irreversible damage.

Understanding the Skin's Scaffolding: Collagen and Elastin

To comprehend smoking's impact, one must first understand the skin's dermal matrix. The dermis, the skin's thick middle layer, is primarily composed of two critical proteins: collagen and elastin. Collagen provides tensile strength and structure, acting as the sturdy framework. Elastin, as the name implies, confers elasticity—the ability to stretch and snap back to its original form. Elastic fibers, which are complex structures made of elastin and microfibrils, form a vast, interconnected network throughout the dermis. This network is the reason youthful skin can be pinched and pulled yet return smoothly to its position. The density, organization, and integrity of these elastic fibers are paramount for maintaining skin tone and preventing sagging.

The Assault on Elastin: A Multi-Pronged Attack

Smoking introduces a cocktail of over 7,000 chemicals, including nicotine, carbon monoxide, and numerous free radicals, into the bloodstream. This toxic mixture orchestrates a multi-faceted attack on the dermal elastic fiber network through several interconnected mechanisms.

Direct Biochemical Degradation: Tobacco smoke is a potent source of free radicals, highly unstable molecules that cause oxidative stress. This oxidative damage directly injures fibroblasts, the specialized cells responsible for synthesizing both collagen and elastin. When fibroblasts are impaired, their production of new, healthy elastic fibers plummets. Simultaneously, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a family of enzymes that naturally break down old and damaged proteins, are upregulated by smoke exposure. MMPs specifically target elastin and collagen, leading to an accelerated degradation of the existing supportive matrix. The result is a double jeopardy: reduced production of new elastin and increased destruction of the old.

Impaired Microcirculation and Tissue Ischemia: Nicotine is a powerful vasoconstrictor, causing the tiny blood vessels (capillaries) in the skin to narrow. Carbon monoxide from smoke binds to hemoglobin in red blood cells with a much greater affinity than oxygen, drastically reducing the amount of oxygen delivered to tissues. This combination leads to chronic tissue ischemia—a state of oxygen and nutrient deprivation within the skin. Fibroblasts are exceptionally metabolically active and require ample oxygen and nutrients to function. Deprived of these essentials, their synthetic capabilities are severely compromised, further hampering the maintenance and repair of the elastic fiber network.

The Elastosis Enigma: Ironically, while smoking depletes healthy, organized elastic fibers, it can sometimes lead to a pathological condition known as elastosis. This is characterized by the accumulation of thickened, tangled, and degraded elastin material in the dermis. However, this aberrant elastin is dysfunctional. It lacks the proper structure and resilience of healthy elastic fibers and provides no mechanical support. Histological studies of smokers' skin frequently reveal this fragmented, clumped elastotic material, which is visually distinct from the orderly network found in non-smokers. This process is a failed repair response, adding bulk but not function, and is a hallmark of severe solar and tobacco-induced damage.

Chronic Inflammation: Tobacco smoke triggers a persistent, low-grade inflammatory response in the skin. Inflammatory cells release cytokines and enzymes that further contribute to the breakdown of the extracellular matrix and inhibit the synthesis of new elastin. This state of perpetual inflammation creates an environment hostile to tissue regeneration and repair.

The Clinical Manifestations: Beyond "Smoker's Face"

The reduction in elastic fiber density translates directly into the classic clinical signs of "smoker's face," a term coined to describe the characteristic appearance of long-term smokers. These signs are a direct result of the loss of skin recoil and support:

- Premature and Exaggerated Wrinkling: The most visible sign. The loss of elastic rebound means skin creases formed by facial expressions (like squinting from smoke irritation or pursing the lips) become permanently etched. Wrinkles are often more pronounced around the mouth (perioral wrinkles) and eyes (crow's feet).

- Skin Sagging and Loss of Contour: Without a dense network of elastic fibers to provide support, the skin begins to succumb to gravity. This leads to jowling, drooping of the eyelids (ptosis), and a general loss of definition in the jawline and cheekbones.

- Altered Texture: The skin may take on a leathery, atrophic, or gaunt appearance due to the thinning of the dermis and the disorganization of its structural components.

- Delayed Wound Healing: The compromised function of fibroblasts and poor blood flow result in significantly slower healing of wounds and a higher risk of complications, a well-documented phenomenon among surgical patients who smoke.

A Distinct and Additive Damage Profile

It is crucial to note that the elastin damage caused by smoking is distinct from, yet synergistic with, photoaging (aging caused by sun exposure). Both processes involve oxidative stress and MMP activation, but they target the skin in slightly different ways. Studies have shown that the elastic fiber damage in smokers often occurs in deeper layers of the dermis compared to the more superficial damage of photoaging. This means a smoking individual who also has significant sun exposure faces a compounded assault on their skin's infrastructure, leading to dramatically accelerated aging.

Conclusion: An Unarguable Case for Cessation

The link between smoking and the reduction of skin elastic fiber density is not merely a cosmetic concern; it is a definitive pathological process with a clear biochemical basis. Smoking orchestrates a perfect storm of increased degradation, decreased synthesis, impaired blood flow, and chronic inflammation that systematically dismantles the skin's elastic support system. This irreversible damage manifests as premature wrinkling, profound sagging, and a loss of youthful vitality. While topical treatments and cosmetic procedures can attempt to address the surface symptoms, they cannot fully reverse the underlying architectural collapse. The most powerful intervention remains prevention and cessation. Quitting smoking halts the continuous assault, allowing natural repair processes to gradually improve blood flow and reduce oxidative stress, offering the skin its best chance at long-term health and preservation. The evidence is clear: for the sake of overall health and the preservation of the skin's structural integrity, avoiding tobacco is one of the most effective anti-aging strategies available.