The Lingering Cloud: Does Smoking Permanently Damage Taste Buds in People with Multiple Sclerosis?

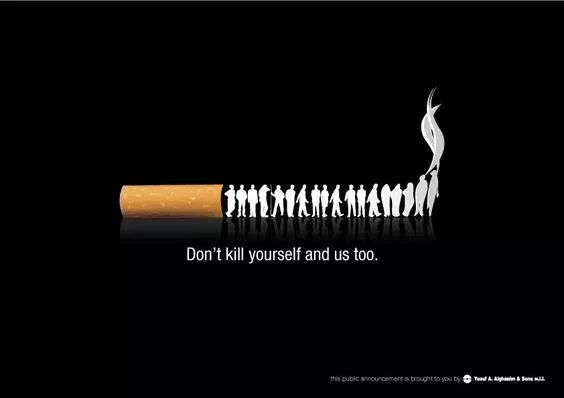

The relationship between smoking and multiple sclerosis (MS) is a complex and well-documented one. Extensive research has established smoking as a significant environmental risk factor for developing MS and is associated with more severe disease progression and increased disability. Beyond these broader neurological impacts, both MS and smoking can individually alter sensory perception, including the sense of taste. This confluence raises a critical question for individuals living with MS who smoke: does this habit cause permanent, irreversible damage to their taste buds, compounding an existing symptom of their disease?

To unravel this, we must first understand the separate effects of MS and smoking on the gustatory system.

The Impact of Multiple Sclerosis on Taste

MS is an autoimmune disorder characterized by the body's immune system attacking the myelin sheath, the protective covering of nerve fibers in the central nervous system. This demyelination disrupts the efficient transmission of nerve signals. Taste perception, or gustation, relies on a intricate neural pathway. Taste buds on the tongue detect chemical stimuli, and this information is transmitted via cranial nerves (specifically the facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves) to the brainstem and ultimately to the gustatory cortex in the brain.

When MS lesions form on these specific pathways—whether on the brainstem, the cranial nerves themselves, or within the brain regions processing taste—the signal can be distorted or lost. This can lead to taste dysfunction, known as dysgeusia. People with MS often report symptoms such as:

- Ageusia: A complete loss of taste.

- Hypogeusia: A reduced ability to taste.

- Parageusia: A persistent metallic, bitter, or otherwise unpleasant taste in the mouth (often called a "phantom taste"). These symptoms can be intermittent or persistent, fluctuating with disease activity and the location of new lesions.

The Impact of Smoking on Taste

Smoking is notoriously harmful to taste buds. The chemicals in tobacco smoke—including tar, nicotine, and various toxins—have a direct, deleterious effect on the tongue. They do this in several ways:

- Direct Damage and Keratinization: Smoke and heat cause physical damage to taste buds. Chronic exposure can lead to keratinization, where the tongue's surface becomes tougher and thicker. This keratin layer acts as a barrier, preventing taste molecules from reaching the taste receptor cells embedded within the buds.

- Reduced Blood Flow: Nicotine is a vasoconstrictor, meaning it narrows blood vessels and reduces blood flow. Taste buds require a rich blood supply to function correctly and regenerate. Impaired circulation starves them of oxygen and nutrients, hindering their health and renewal.

- Altered Saliva Production: Smoking can affect the quantity and quality of saliva, which is essential for dissolving food particles and transporting them to the taste buds.

- Neurological Effects: Nicotine can also interfere with the nervous system, potentially affecting the transmission of taste signals to the brain.

The good news for the general population is that much of smoking's impact on taste is reversible. Upon quitting, the tongue's surface begins to heal. Blood flow improves, keratinization recedes, and taste buds, which regenerate approximately every 10-14 days, can return to a healthier state. Studies show that former smokers often report a significant improvement in taste acuity within weeks to months of cessation.

The Converging Storm: MS and Smoking

For a person with MS, this equation becomes significantly more complicated. The key issue is the distinction between damage and dysfunction.

Smoking likely causes direct, structural damage to the taste buds and their local environment on the tongue. However, the more profound and potentially permanent threat for someone with MS is the neurological damage from both habits combined.

- Exacerbated Neuroinflammation: Smoking promotes systemic inflammation and is a known negative prognostic factor in MS. It can accelerate the formation of new lesions and increase the overall burden of disease in the brain and spinal cord. If a new lesion forms on a crucial part of the gustatory pathway, it could cause a permanent loss of taste signal transmission, irrespective of the health of the tongue's taste buds. The taste buds might be perfectly capable of detecting stimuli, but the message cannot get through to the brain.

- Cumulative Damage: Think of it as a two-pronged attack. Smoking damages the peripheral system (the taste buds), while MS damages the central nervous system (the wiring to the brain). The combination maximizes the risk of taste impairment. Even if someone quits smoking and their taste buds recover fully, a pre-existing MS-related lesion on the brainstem could still prevent normal taste perception permanently.

- Masking and Interaction: A smoking-related taste distortion (e.g., a constant dullness) could mask or interact with an MS-related taste symptom (e.g., a metallic phantom taste), creating a complex and distressing sensory experience that is difficult to treat.

Conclusion: Permanence Lies in the Nerves

So, does smoking permanently damage taste buds in people with MS? The answer is nuanced.

The taste buds themselves likely retain their capacity for regeneration even in individuals with MS. Therefore, the damage caused directly by smoke should not be considered "permanent" in a biological sense; cessation should still allow for some degree of recovery at the level of the tongue.

However, the overall ability to perceive taste is at a far greater risk of permanent impairment. The true permanence comes from the potential for smoking to exacerbate the underlying MS disease process, leading to irreversible neurological damage within the taste pathways of the central nervous system. A healed tongue is of little use if the cable to the brain has been severed by a demyelinating lesion.

Therefore, for a person with MS who smokes, quitting remains one of the most critical actions they can take for their overall health and disease prognosis. While it may not reverse existing neural damage, it can halt the accelerated inflammatory cycle that leads to further permanent lesions. Protecting the brain's wiring is ultimately the most effective strategy for preserving all sensory functions, including the cherished ability to enjoy the flavor of food.