The Lingering Cloud: Investigating Gender Disparities in Smoking's Impact on Taste Perception

The act of smoking is a well-documented assault on human health, with its detrimental effects on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems being the focus of extensive public health campaigns. However, a more subtle, yet profoundly impactful, consequence lies in its disruption of one of our most fundamental senses: taste. The question of whether this damage is more severe and permanent in men than in women delves into a complex interplay of physiology, behavior, and sociocultural factors. While a simple, definitive answer remains elusive, the evidence suggests that while the biological mechanisms of damage are likely similar, the ultimate impact on taste buds may indeed manifest differently across genders due to a confluence of these variables.

To understand the potential for permanent damage, one must first grasp how smoking impairs taste function. Taste buds, clusters of sensory cells located primarily on the tongue, are not static entities; they undergo a constant cycle of renewal approximately every 10 to 14 days. This natural regeneration is key to maintaining a sharp sense of taste. The primary culprits in cigarette smoke—nicotine, tar, and various other toxic chemicals—interfere with this process in several ways. They can directly damage the delicate structure of the taste buds themselves, thinning the epithelium and altering their morphology. Furthermore, these substances impair blood flow to the taste buds, starving them of essential oxygen and nutrients needed for healthy function and regeneration. Smoke also causes a constant, low-grade inflammation in the oral cavity, which can further disrupt the sensitive signaling pathways between the taste receptors and the brain.

The term "permanent damage" is critical here. Short-term effects are almost universal among smokers: a noticeable dulling of taste, often leading to a preference for saltier, sweeter, or more intensely flavored foods to compensate. This is often reversible upon cessation, as the body's regenerative processes, freed from the constant toxic insult, can restore function over weeks or months. Permanent damage implies a point of no return—where the cumulative injury has either destroyed the stem cells responsible for regenerating taste buds or caused such significant neurological or vascular damage that full recovery is impossible. This threshold is highly individualistic, influenced heavily by the duration and intensity of smoking (pack-years), genetic predisposition, and overall oral health.

When examining gender differences, the biological evidence presents a nuanced picture. There is no conclusive scientific consensus that male taste buds are inherently more vulnerable to the toxins in smoke than female taste buds at a cellular level. The fundamental mechanism of damage—chemical irritation and reduced blood flow—should, in theory, affect all human taste buds similarly. However, several factors could lead to a disparity in perceived and actual permanent damage.

Firstly, behavioral patterns in smoking differ significantly between men and women. Historically, and still in many regions, men tend to be heavier smokers. They often start smoking earlier, smoke more cigarettes per day, and are less likely to attempt quitting. This higher cumulative exposure to carcinogens and toxins significantly increases the risk of crossing the threshold into permanent damage. A man with a 40-pack-year history is at a far greater risk of irreversible taste bud impairment than a woman with a 15-pack-year history. Therefore, the observed greater damage in men may be more a function of dosage and duration than an inherent biological susceptibility.

Secondly, the role of hormones cannot be ignored. Estrogen, in particular, has been shown to have a protective effect on neural function and may play a role in sensory perception, including taste. Some studies suggest that women generally have a higher density of taste buds and a more acute sense of taste than men, a phenomenon that may be influenced by hormonal fluctuations. It is plausible, though not definitively proven, that estrogen could offer a degree of protection against the neurodegenerative aspects of smoke-induced damage, potentially slowing the progression towards permanence. This hormonal influence could mean that for the same level of smoking exposure, a woman's taste perception might degrade at a slower rate than a man's. However, this potential advantage may diminish after menopause when estrogen levels decline.

Thirdly, confounding lifestyle factors complicate the comparison. Men who smoke often have other habits that synergistically damage taste perception, such as higher rates of heavy alcohol consumption. Alcohol is itself a desiccant and irritant that can compound the damage caused by smoking. Dietary choices may also play a role. If men are more likely to consume a diet high in processed foods regardless of smoking status, the baseline for their taste perception might already be different, making the incremental damage from smoking more pronounced or noticeable.

Conversely, research into smoking cessation reveals another layer of complexity. Some studies indicate that women find it harder to quit smoking than men, often citing weight control and stress management as significant barriers. If women are smoking for a longer portion of their lives despite potentially smoking fewer cigarettes per day, their long-term exposure could still be significant, increasing their risk of permanent damage. Furthermore, the motivation to quit due to changes in taste might be different. A man who heavily associates smoking with socializing or work breaks might be less bothered by a dulled palate than a woman for whom food preparation and enjoyment are central to her daily life or cultural role.

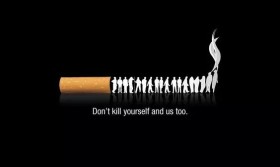

In conclusion, the question of whether smoking causes more permanent taste bud damage in men than women cannot be answered with a straightforward "yes" or "no." The direct cytotoxic effects of smoke are likely gender-blind. However, the ultimate outcome—the degree and permanence of taste impairment—is heavily mediated by external factors where significant gender disparities exist. Men, on average, through heavier smoking patterns and associated lifestyle choices, may indeed reach the threshold of permanent damage more frequently. Yet, this is not an inevitability of their biology but rather a consequence of behavior. A female light smoker is at less risk than a male heavy smoker, but a female heavy smoker is certainly at high risk. The most critical finding is that for both genders, prolonged smoking poses a grave threat to the vitality of taste perception. The best strategy for preserving this essential sense is not to gamble on potential gender-based advantages but to avoid smoking altogether or to cease the habit before the delicate balance of taste bud regeneration is irrevocably lost. The cloud smoking casts over taste may linger longer for some, but it darkens the palate of all who inhale.