The Palate's Crossroads: Does Early Smoking Cessation Avert Permanent Taste Bud Damage?

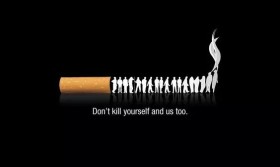

The decision to quit smoking is a monumental step towards reclaiming one's health, often motivated by the desire to avoid life-threatening conditions like lung cancer, heart disease, and emphysema. Yet, among the myriad of benefits, the restoration of taste and smell is one of the most immediate and gratifying rewards reported by former smokers. This sensory reawakening raises a critical question: if an individual quits smoking early enough, can they completely prevent the permanent damage to their delicate taste buds? The answer lies at the complex intersection of biology, duration of exposure, and the remarkable capacity of the human body for repair.

To understand the potential for damage, we must first appreciate the intricate machinery of taste. Taste buds are not simple, static bumps on the tongue; they are sophisticated sensory organs composed of approximately 50 to 150 specialized cells clustered within the papillae. These cells have a rapid turnover rate, regenerating approximately every 10 to 14 days. This constant renewal is the body's first line of defense and the primary source of hope for recovery. Taste perception itself is a multi-sensory experience, heavily reliant on our sense of smell (olfaction). The "flavor" of food is a combination of the five basic tastes detected by the tongue—sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami—and the thousands of aromatic compounds perceived by the olfactory receptors in the nose.

Smoking launches a relentless, multi-pronged assault on this delicate system. The primary culprit is the vast cocktail of toxic chemicals present in cigarette smoke, including tar, nicotine, hydrogen cyanide, and formaldehyde.

The Mechanisms of Damage

The damage occurs through several key mechanisms:

-

Direct Chemical Irritation and Coating: Hot smoke and tar directly bathe the tongue and oral cavity. Tar, a sticky substance, can physically coat the taste buds, creating a barrier that impedes their ability to come into contact with food molecules. This is akin to trying to taste a delicate spice through a layer of sludge. This coating effect dulls taste perception almost immediately after smoking.

-

Impaired Blood Flow and Oxygen Supply: Nicotine is a potent vasoconstrictor, meaning it causes blood vessels to narrow. This reduces blood flow to the tiny capillaries that supply the taste buds with essential oxygen and nutrients. Chronically deprived of adequate circulation, the taste buds cannot function optimally or regenerate healthily. They may become shriveled, flattened, and less responsive.

-

Damage to Olfactory Function: A significant portion of what we perceive as taste is actually smell. Smoke particles travel through the back of the throat to the olfactory epithelium, damaging or even destroying the sensitive nerve cells responsible for detecting odors. This loss of smell, known as anosmia or hyposmia, profoundly flattens the overall flavor experience. A strawberry may only register as "sweet" without its characteristic aromatic notes.

-

Chronic Inflammation and Structural Changes: Long-term exposure to smoke irritants leads to a state of chronic inflammation in the oral mucosa. This can cause changes in the shape and density of the papillae on the tongue. Studies have shown that smokers often have a lower density of fungiform papillae (which house taste buds) compared to non-smokers. Furthermore, smoking can directly damage the taste receptor cells themselves, altering their structure and function.

The Critical Window: Early Cessation and the Body's Resilience

Given the rapid regeneration cycle of taste bud cells, the human body possesses a significant capacity for healing once the source of the aggression is removed. This is where the timing of cessation becomes paramount.

When a person quits smoking, the onslaught of toxins ceases. The body immediately begins its repair work. Within as little as 48 hours, nerve endings begin to regenerate, and the sense of smell and taste start to improve. The tar coating begins to clear, and blood circulation to the gums and taste buds gradually normalizes. For many new ex-smokers, this period is marked by a sensory "reboot," where food suddenly seems more vibrant and flavorful, sometimes overwhelmingly so.

For individuals who quit smoking after a relatively short duration—for instance, a few years—the likelihood of a full, or near-full, recovery of taste function is high. The damage inflicted is primarily functional and reversible: the coating of tar washes away, inflammation subsides, and with a restored blood supply, the naturally regenerative taste bud cells can repopulate effectively. The olfactory nerves, while slower to heal, also have a capacity for repair if the damage is not too severe. In these cases, quitting early can indeed prevent what would have become permanent damage had the habit continued.

The Threshold of Permanence: When is the Damage Irreversible?

The concept of "early" is relative and varies from individual to individual, influenced by genetic predisposition, overall health, and smoking intensity (number of cigarettes per day). However, the risk of permanent damage increases significantly with the duration and intensity of smoking.

After decades of heavy smoking, the cumulative assault can cross a threshold. The chronic inflammation and repeated damage may lead to more profound, structural changes. While taste buds themselves will still regenerate after quitting, the environment in which they exist may be permanently altered. The papillae that house the taste buds may not fully recover their original density or structure. More critically, the olfactory nerve cells in the nose can sustain irreversible damage. Unlike taste bud cells, olfactory neurons are a specialized type of nerve cell with a more limited capacity for regeneration. If these cells are destroyed over a long period, the loss of smell can be permanent.

This permanent olfactory damage is the primary reason why some long-term ex-smokers never fully regain their original sense of taste, even after quitting for many years. They can detect the basic tastes on their tongue, but the complex symphony of flavor orchestrated by smell remains muted. The damage has moved from a reversible, functional level to an irreversible, structural one.

Conclusion: A Powerful Intervention, Not Always a Perfect Cure

In conclusion, the question of whether quitting smoking early prevents permanent taste bud damage can be answered with a qualified yes. Early cessation is the single most effective action to preserve and restore sensory function. For those who smoke for a limited number of years, the body's innate regenerative powers are typically robust enough to reverse most, if not all, of the damage, allowing for a full return of taste and smell.

However, it is crucial to understand that "early" is a key determinant. The longer and more heavily one smokes, the greater the risk of crossing a line into permanent damage, particularly to the olfactory system. Quitting smoking at any stage will undoubtedly lead to significant improvement and halt further degradation, but it may not be a complete cure if the damage has become structural.

Therefore, the act of quitting should be viewed not just as a prevention for catastrophic diseases, but as a vital intervention for preserving the simple, profound joys of life—like savoring a perfectly ripe piece of fruit or the rich aroma of coffee. While the palate may be resilient, it is not invincible. The best strategy to ensure its lifelong health is to never start smoking at all, and the second-best strategy is to extinguish the habit as soon as possible.