Smoking Prolongs Acute Asthma Exacerbation Recovery Time: An In-Depth Analysis

The Detrimental Impact of Tobacco Smoke on Asthma Recovery

Introduction

Asthma, a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways, affects millions worldwide and is characterized by recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and coughing. An acute asthma exacerbation represents a severe worsening of these symptoms, often requiring urgent medical intervention. While numerous triggers, such as allergens, pollution, and respiratory infections, are known to precipitate these attacks, cigarette smoking stands out as a major, yet modifiable, risk factor. This article delves into the multifaceted mechanisms through which active smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke significantly prolong the recovery time from an acute asthma exacerbation, creating a substantial barrier to effective disease management.

Understanding the Pathophysiology: A Dual Assault

To comprehend how smoking impedes recovery, one must first understand the baseline pathophysiology of asthma and the additional damage inflicted by tobacco smoke.

1. The Asthmatic Airway in Exacerbation

During an acute exacerbation, the airways undergo a pronounced inflammatory response. Eosinophils, neutrophils, and other inflammatory cells infiltrate the airway walls. This leads to:

- Bronchoconstriction: The smooth muscles surrounding the airways tighten abruptly.

- Mucous Hypersecretion: Goblet cells produce excessive, thick mucus that plugs the airways.

- Airway Edema: The lining of the airways becomes swollen due to inflammation and fluid buildup.

Recovery involves resolving this inflammation, relaxing the bronchial muscles, and clearing the mucus.

2. The Added Insult of Tobacco Smoke

Tobacco smoke is a complex mixture of over 7,000 chemicals, hundreds of which are toxic and about 70 known to cause cancer. It delivers a dual assault to the asthmatic lung:

- Exacerbated Inflammation: Smoke activates the innate immune system, leading to a massive influx of neutrophils and macrophages. This neutrophilic inflammation is particularly resistant to standard corticosteroid treatments, the cornerstone of asthma therapy. The result is a more intense and persistent inflammatory state that takes longer to subside.

- Impaired Ciliary Clearance: The airways are lined with tiny hair-like structures called cilia, which function to sweep mucus and debris out of the lungs. Tobacco smoke paralyzes and destroys these cilia. Consequently, the thick mucus produced during an asthma attack cannot be cleared effectively, lingering in the airways and prolonging obstruction and symptoms.

Mechanisms of Prolonged Recovery

The interaction between asthma's pathophysiology and smoke-induced damage creates a perfect storm that delays healing through several key mechanisms.

1. Corticosteroid Insensitivity

This is perhaps the most significant mechanism behind prolonged recovery. Corticosteroids work by switching off multiple inflammatory genes. However, tobacco smoke alters the molecular environment within lung cells in two critical ways:

- It reduces the activity and expression of the glucocorticoid receptor to which steroids bind, making the cells less responsive.

- It activates pro-inflammatory pathways that steroids cannot easily suppress.As a result, the standard high-dose steroid treatments administered during an exacerbation are less effective. The inflammation persists, and the patient's symptoms, such as wheezing and shortness of breath, resolve at a much slower rate, often requiring longer hospital stays and higher medication doses.

2. Oxidative Stress and Tissue Damage

Tobacco smoke is a powerful source of oxidative stress, introducing a high burden of free radicals that directly damage airway epithelial cells. This damage:

- Disrupts the protective barrier of the airways, making them more hyperresponsive and prone to further constriction.

- Perpetuates the inflammatory cycle, as the body attempts to repair the injured tissue.This ongoing cycle of injury and repair consumes energy and resources that would otherwise be dedicated to resolving the acute exacerbation, thereby extending the recovery timeline.

3. Increased Risk of Respiratory Infections

Smokers are more susceptible to viral and bacterial respiratory infections, which are common triggers for asthma attacks. Smoking impairs the function of immune cells like natural killer cells and macrophages, weakening the lung's defense system. A patient recovering from an exacerbation is in a vulnerable state, and a new infection, acquired during this period, can set back recovery significantly or even precipitate a second exacerbation, creating a vicious cycle of illness.

4. Structural Remodeling

Chronic exposure to tobacco smoke accelerates airway remodeling—a process where repeated cycles of injury and inflammation lead to structural changes like thickening of the airway wall, fibrosis, and hyperplasia of smooth muscle. In a smoker with asthma, exacerbations contribute to this remodeling. Over time, the airways become permanently narrowed and less responsive to bronchodilators. This means that with each subsequent exacerbation, the baseline lung function is lower, and the ability to recover fully to pre-exacerbation levels is diminished. Recovery becomes not only slower but also less complete.

The Role of Secondhand Smoke

It is crucial to emphasize that the risks are not confined to active smokers. Secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure, especially in children and non-smoking adults with asthma, is a major contributor to exacerbation severity and delayed recovery. SHS contains many of the same harmful chemicals as directly inhaled smoke. Children with asthma exposed to SHS have been shown to have more frequent emergency department visits, longer durations of symptoms during an attack, and a greater need for intensive treatment compared to those in smoke-free environments. For a recovering asthmatic, ongoing SHS exposure is akin to continuously poking an open wound, preventing the healing process from commencing effectively.

Clinical and Quality of Life Implications

The prolongation of recovery time has profound implications:

- Increased Healthcare Burden: Longer hospital admissions, more frequent follow-up visits, and higher doses of medications strain healthcare systems and increase costs.

- Reduced Lung Function: Slower recovery often means a failure to return to baseline lung function, leading to a gradual, step-wise decline in overall respiratory capacity.

- Diminished Quality of Life: Patients endure a longer period of disability, missing work or school and being unable to participate in daily activities. This prolonged morbidity also contributes to anxiety and depression.

Conclusion and a Path Forward

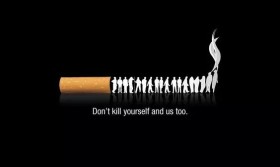

The evidence is unequivocal: smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke actively hinder the recovery from an acute asthma exacerbation. Through mechanisms like corticosteroid insensitivity, enhanced inflammation, oxidative stress, and increased infection risk, tobacco smoke transforms a manageable acute event into a protracted struggle for health.

Addressing this issue requires a multi-pronged approach. Smoking cessation is the single most effective intervention. Healthcare providers must integrate robust smoking cessation counseling and support into the management of every asthmatic patient who smokes, especially following an exacerbation. Creating smoke-free environments for children and adults with asthma is equally critical for public health. Ultimately, understanding the profound link between smoking and prolonged asthma recovery underscores the importance of tobacco control not just as a general health measure, but as a specific and vital component of effective asthma therapy. Quitting smoking is not merely a lifestyle recommendation; it is a fundamental therapeutic strategy for achieving faster, more complete recovery and better long-term asthma control.