The Lingering Smoke: How Even Light Smoking Alters Your Sense of Taste

For decades, the image of a smoker has been intertwined with a diminished sense of taste and smell. The heavy, pack-a-day habit is widely recognized for its ability to dull the palate, making food seem bland and unappealing. But what about the casual smoker, the individual who indulges in fewer than twenty cigarettes a day? Does this moderate level of smoking cause permanent, irreversible damage to the delicate structures of the taste buds, or is the effect merely a temporary nuisance that fades with abstinence? The answer, rooted in the complex biology of taste and the insidious nature of tobacco smoke, is more nuanced than a simple yes or no.

To understand the impact, we must first appreciate what taste buds are and how they function. Contrary to popular belief, taste buds are not the visible bumps on your tongue; those are papillae. The taste buds themselves are microscopic clusters of 50-100 specialized cells nestled within these papillae. These cells are responsible for detecting the five basic tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. Crucially, taste bud cells are not permanent. They have a short life cycle, regenerating approximately every 10 to 14 days. This constant renewal is a key factor in the debate about permanent damage.

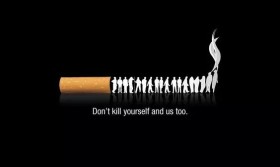

Tobacco smoke is a toxic cocktail of over 7,000 chemicals, including nicotine, tar, and hydrogen cyanide. When inhaled, these compounds do not just travel to the lungs; they also come into direct contact with the oral cavity. The damage inflicted on the sense of taste occurs through several interconnected mechanisms, regardless of the number of cigarettes smoked.

First, and most directly, smoke causes physical and chemical irritation to the taste buds. The heat and toxic chemicals can scorch and inflame the delicate papillae, impairing the function of the taste receptor cells housed within. Nicotine itself is a vasoconstrictor, meaning it tightens blood vessels and reduces blood flow. Since taste buds require a rich blood supply for oxygen and nutrient delivery to support their rapid regeneration, chronic reduction in circulation can starve them, leading to weaker, less sensitive cells. This is akin to trying to maintain a lush garden while slowly restricting its water supply.

Second, smoking directly interferes with the sense of smell, or olfaction, which is intrinsically linked to taste. What we perceive as "flavor" is actually a combination of taste (from the tongue) and aroma (detected by olfactory receptors in the nose). This is why food seems tasteless when you have a cold. Smoking damages these olfactory receptors and the lining of the nasal passages, severely hampering the ability to detect subtle aromas. Consequently, even if the taste buds are somewhat functional, the overall flavor experience is dramatically muted.

Third, smoking alters saliva production and composition. Saliva is essential for taste; it acts as a solvent, dissolving food molecules so they can interact with the taste receptors. Smoking can lead to dry mouth (xerostomia) and change the chemical makeup of saliva, creating a barrier that prevents taste compounds from reaching the buds effectively.

Now, to the central question: if you smoke less than a pack a day, is this damage permanent? The concept of "permanence" must be carefully defined in the context of constantly regenerating cells. The damage is unlikely to be permanent in the sense of the taste buds being physically scarred for life. The body's remarkable regenerative capacity offers a pathway to recovery. Numerous studies and anecdotal reports from former smokers confirm that taste and smell sensitivity significantly improve after quitting. Within days, inflammation reduces. Within weeks, as blood flow normalizes and a new, healthier generation of taste buds forms, individuals often report a "rediscovery" of flavors.

However, to equate this recovery with a complete absence of long-term consequences would be misleading. The key factor is the duration of the smoking habit, not just the daily quantity. A person who smokes ten cigarettes a day for twenty years has subjected their taste buds to 20 years of chronic, low-grade assault. This long-term exposure can lead to changes that are not instantly reversible.

While the individual taste buds may regenerate, the cumulative damage can affect the underlying support structures and nerve endings. Prolonged inflammation can cause subtle scarring or metaplasia (a change in cell type) in the oral tissues. Furthermore, the chronic desensitization of the olfactory system may lead to a long-lasting, if not entirely permanent, reduction in peak sensitivity. Think of it as a musical instrument that has been slightly out of tune for years. Even after it is retuned, it might not hold its pitch as perfectly as a brand-new instrument, or a musician who has played it out of tune for so long may have to relearn how to play it correctly.

For the light smoker, the damage is often more about a persistent suppression of function rather than outright destruction. The system is kept in a state of sub-optimal performance. The regeneration process is constantly fighting an uphill battle against a daily influx of toxins. Therefore, the sense of taste may not be "permanently damaged" in a literal sense, but it is certainly "chronically impaired" for as long as the smoking habit continues.

The good news is that the human body is resilient. Quitting smoking at any point allows for substantial healing. The improvement can be dramatic and life-changing, leading to a greater appreciation for food and often contributing to healthier eating habits. The risk of permanent, noticeable deficit is much lower for a light smoker who quits after a few years compared to a heavy, lifelong smoker.

In conclusion, smoking less than a pack a day does not typically result in the kind of absolute, irreversible destruction of taste buds that the word "permanent" might imply. The biological reality of cellular regeneration offers a powerful hope for recovery. However, it unequivocally causes significant and persistent damage for the duration of the habit. It chronically impairs taste function by directly damaging taste buds, restricting their blood supply, and crippling the allied sense of smell. The long-term health of your palate is not determined by a single day's cigarette count, but by the relentless, cumulative toll of the habit over time. The most profound damage, therefore, may not be to the cells themselves, but to the years of rich sensory experience lost to the lingering haze of smoke.