The Point of No Return: When Does Temporary Taste Bud Damage from Smoking Become Permanent?

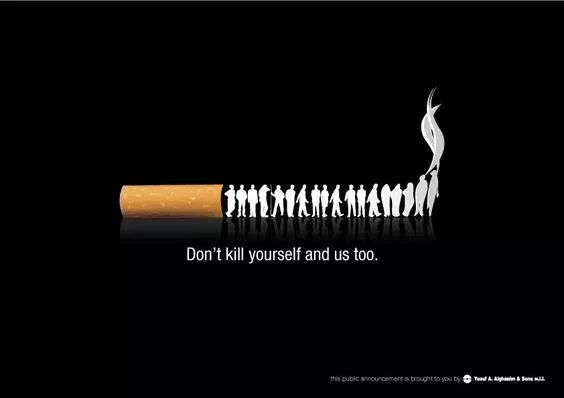

For generations, the act of smoking has been synonymous with a myriad of well-documented health risks, primarily centered on lung cancer, heart disease, and respiratory failure. However, a more subtle yet profoundly impactful consequence often flies under the radar: the gradual erosion of the sense of taste and smell. Every smoker is familiar with the initial experience—the dulling of flavors, the metallic aftertaste, the inability to fully appreciate a fine meal. This is often dismissed as a temporary nuisance. But a critical question lingers for both current and former smokers: at what point does this temporary sensory impairment cross the threshold into permanent, irreversible damage?

To understand this transition, we must first delve into the delicate biology of taste. What we commonly refer to as "taste buds" are part of a sophisticated sensory system. The visible taste buds on the tongue are collections of 50-100 specialized epithelial cells. These are not the sole players; smell, or olfaction, is intrinsically linked. Aromas travel to the olfactory receptors high in the nasal cavity, and the combination of taste (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, umami) and smell creates the rich, complex experience of flavor. Crucially, taste bud cells have a short lifespan, regenerating approximately every 10 to 14 days. This constant renewal is the body’s built-in repair mechanism and the source of hope for recovery.

Smoking launches a multi-faceted assault on this system. The primary culprit is the vast cocktail of chemicals in tobacco smoke, with tar and nicotine being the principal offenders.

- Coating and Blocking: Tar, a sticky residue, physically coats the tongue and smothers the taste buds. It acts as a barrier, preventing flavor molecules from reaching the sensory cells. Simultaneously, smoke irritates and inflames the nasal passages and olfactory epithelium, impairing the sense of smell and, by extension, the perception of flavor.

- Vascular Constriction: Nicotine is a potent vasoconstrictor, meaning it causes blood vessels to narrow. This reduces blood flow to the tiny capillaries that supply the taste buds with essential oxygen and nutrients. A starved taste bud cannot function optimally or regenerate effectively.

- Chemical Alteration: Some chemicals in smoke can directly alter the chemistry of saliva or interfere with the receptor proteins on the taste cells themselves, changing how they respond to basic tastes. This often leads to the characteristic metallic or bitter aftertaste reported by smokers.

- Thermal Damage: The heat from inhaling hot smoke can cause low-grade thermal damage to the sensitive tissues of the mouth and tongue, further contributing to cellular stress.

In the early stages of smoking, the damage is overwhelmingly temporary. A person who smokes occasionally may notice a dulled palate the next day, but as the tar is cleared by saliva and the taste buds complete their natural regeneration cycle over the following week or two, function typically returns to near-normal. This cycle of damage and repair can continue for years, creating a deceptive sense of reversibility.

The pivotal shift from temporary to permanent damage is not marked by a specific date on the calendar but is rather a gradual process dictated by cumulative exposure—most accurately measured in "pack-years" (number of packs smoked per day multiplied by the number of years smoked). As smoking continues, the chronic nature of the assault begins to overwhelm the body’s regenerative capabilities.

Several key changes occur that signal a move toward permanence:

- Basement Membrane Damage: The most critical factor is damage to the basement membrane upon which new taste bud cells are generated. Think of this membrane as the soil from which new plants (taste cells) grow. Chronic inflammation and chemical exposure can scar and damage this foundational layer. If the "soil" is ruined, even if smoking ceases, the ability to regenerate fully functional taste buds is severely compromised.

- Chronic Inflammation: Persistent irritation leads to a state of chronic inflammation in the oral mucosa and nasal passages. This inflammatory environment releases cytokines that can be toxic to delicate sensory cells and can disrupt the signaling pathways necessary for normal taste perception.

- Neuropathy: The ultimate signal from a taste bud to the brain is carried via nerve fibers. Long-term exposure to neurotoxicants in smoke can damage these nerves. While taste bud cells can regenerate, nerve damage is often much more difficult, if not impossible, to reverse.

So, when is the point of no return? There is no universal answer, as individual genetics, overall health, and dietary habits play a role. However, clinical observations suggest that significant, often permanent, loss becomes highly probable after 20 to 30 pack-years of smoking. For a person smoking one pack a day, this translates to 20-30 years of smoking. By this point, the cumulative damage to the regenerative infrastructure and nerves is often too great for a full recovery.

The evidence for this is seen in studies of long-term quitters. Individuals who quit smoking after a few years typically report a dramatic return of their sense of taste and smell within weeks to months. The body, relieved of the constant assault, can effectively clear tar and regenerate healthy cells. In contrast, those who smoked heavily for decades often report only a partial improvement. They may regain the ability to detect basic tastes more strongly, but the nuanced, complex flavors never fully return. The damage has become ingrained.

It is also vital to distinguish between damage caused by smoking and age-related taste loss (presbygeusia). While taste function naturally declines with age, smoking accelerates this process dramatically. A 60-year-old former heavy smoker will likely have a much poorer sense of taste than a non-smoking 60-year-old.

The journey from temporary taste bud irritation to permanent sensory loss is a silent, insidious progression. It is a testament to the body’s remarkable resilience that it fights for so long to repair the damage. But resilience has its limits. The transition to permanence is a slow fade, not a sudden switch, dictated by the relentless accumulation of toxic insults. This understanding serves as a powerful, sensory-based incentive for cessation. The ability to savor food is one of life’s fundamental pleasures. The best way to ensure it is never permanently lost is to end the assault before the body’s capacity for repair is exhausted. The window for a full recovery is wide open for years, but it does, inevitably, begin to close.