Unveiling the Link: How Smoking Influences Intestinal Metaplasia Progression in Atrophic Gastritis

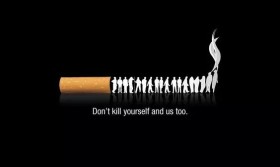

If you or someone you care about is living with a diagnosis of atrophic gastritis, you're likely navigating a world of complex medical terms and concerns about long-term health. One of the most crucial developments in this condition is the emergence of intestinal metaplasia, a change that significantly alters the stomach's lining. While several factors are at play, a growing body of compelling evidence points to a major, modifiable risk factor: smoking. This article delves deep into the connection between smoking and the degree of intestinal metaplasia in atrophic gastritis, empowering you with the knowledge to make informed decisions for your digestive wellness.

First, let's demystify the core conditions. Atrophic gastritis is a chronic inflammation of the stomach lining that leads to the loss of specialized glandular cells. Think of these cells as the stomach's workforce, producing essential gastric juices and acids for digestion. When these cells atrophy or waste away, the stomach's ability to function properly is compromised. This condition often arises from long-term infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria or as an autoimmune disorder.

A more advanced stage within this spectrum is intestinal metaplasia (IM). Here, the body attempts to adapt to the ongoing injury. The cells that normally line the stomach are gradually replaced by cells that resemble those found in the intestine. While this might sound like a clever adaptation, it's a double-edged sword. This altered landscape of the gastric mucosa is widely recognized as a precancerous lesion, meaning it carries a significantly increased risk of developing into gastric cancer over time. The "degree" or "extent" of intestinal metaplasia is critical; more extensive metaplasia correlates with a higher risk profile.

So, where does smoking fit into this picture? It's far more than just a habit that affects the lungs. The chemicals in tobacco smoke are absorbed into the bloodstream and travel throughout the body, including to the delicate lining of the digestive tract. When you smoke, a cocktail of over 7,000 chemicals, including nicotine, tar, and numerous carcinogens, comes into direct contact with your gastric environment.

The biological mechanisms through which smoking exacerbates atrophic gastritis and accelerates the progression of intestinal metaplasia are multifaceted. One primary pathway is through the profound reduction in blood flow to the gastric mucosa. Nicotine is a potent vasoconstrictor, meaning it causes blood vessels to narrow. This reduces the delivery of oxygen and essential nutrients to the stomach lining, impairing its ability to repair itself and maintain a healthy barrier. This chronic state of ischemia, or oxygen shortage, creates a hostile environment that fuels cellular damage and death.

Furthermore, tobacco smoke is a powerful stimulant of inflammatory processes. It triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are signaling molecules that perpetuate inflammation. In a condition like atrophic gastritis, which is already defined by inflammation, smoking effectively pours fuel on the fire. This sustained inflammatory assault not only speeds up the atrophy of gastric glands but also creates the precise conditions that favor the emergence of intestinal metaplasia as a survival response by the tissue.

Perhaps one of the most direct links involves the formation of carcinogenic compounds. Nitrates present in tobacco smoke can be converted into N-nitroso compounds within the stomach. These compounds are potent carcinogens that can directly damage the DNA of gastric cells. This genetic damage can disrupt normal cell cycle regulation and apoptosis (programmed cell death), pushing cells down the path of abnormal transformation—the very essence of the metaplastic process. This explains why smokers with atrophic gastritis are often found to have a higher grade and more extensive degree of intestinal metaplasia compared to non-smokers.

The impact of smoking on the risk and severity of intestinal metaplasia is not just theoretical; it's consistently backed by clinical observations. Numerous endoscopic and histological studies have demonstrated a clear dose-response relationship. This means that the risk of developing extensive intestinal metaplasia increases with the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the total number of years a person has smoked. Heavy, long-term smokers consistently show more severe pathological changes in their gastric mucosa. This is a critical point for risk stratification in clinical practice.

Moreover, the combination of smoking and an H. pylori infection appears to be particularly deleterious. H. pylori is a primary driver of atrophic gastritis, and smoking acts as a powerful co-factor, synergistically accelerating the damage. The two together create a perfect storm for the rapid progression from simple inflammation to atrophy, and then to widespread intestinal metaplasia. For patients diagnosed with H. pylori, smoking cessation becomes an equally vital part of the eradication and management strategy.

Understanding this link is not meant to cause alarm but to highlight a profound opportunity for intervention. The progression from atrophic gastritis to intestinal metaplasia and potentially to gastric cancer is often a slow process, spanning years or even decades. This provides a crucial window for action. Quitting smoking is the single most effective step a person with atrophic gastritis can take to alter the course of their disease. The benefits begin almost immediately.

Upon cessation, the constant barrage of toxins ceases. Blood flow to the gastric lining improves, allowing for better cellular repair. The chronic inflammatory state begins to subside. While existing metaplastic changes may not fully reverse, studies suggest that the progression can be halted or significantly slowed. This dramatically reduces the long-term risk of gastric cancer development. The body's remarkable resilience means that it's never too late to quit and derive health benefits.

For individuals managing atrophic gastritis, a comprehensive approach is essential. This includes regular endoscopic surveillance to monitor the extent of atrophy and the degree of intestinal metaplasia, adherence to any prescribed treatments for H. pylori, and dietary modifications. However, integrating smoking cessation into this management plan is non-negotiable for optimal outcomes. It is a powerful, evidence-based strategy to protect your stomach health.

In conclusion, the relationship between smoking and the severity of intestinal metaplasia in atrophic gastritis is undeniable and mechanistically sound. Smoking acts as a powerful accelerator, driving inflammation, causing direct cellular damage, and fostering an environment where precancerous changes thrive. If you are living with atrophic gastritis, viewing smoking cessation not just as a general health recommendation, but as a specific and targeted therapy for your condition, can be a transformative perspective. By choosing to quit, you are actively taking control, intervening in the disease pathway, and making the most significant investment in your long-term gastrointestinal health and overall well-being. Your stomach's future is, to a large extent, in your hands.