The Hidden Cost of a Habit: How Smoking Skyrockets the Price of Healing from Diving Injuries

It's a scenario that plays out in emergency departments around the world, often with a sense of bewildering urgency. A scuba diver surfaces from a seemingly routine dive, only to be gripped by a sharp, stabbing pain in their chest, accompanied by shortness of breath. The diagnosis: pneumothorax, more commonly known as a collapsed lung, specifically induced by barotrauma—the pressure change experienced during ascent. This is a serious medical situation for anyone, demanding immediate attention and complex care. But for a patient who is a smoker, the entire equation changes dramatically. The treatment pathway becomes longer, more invasive, and exponentially more expensive. The simple, harsh truth is that a history of smoking doesn't just increase the risk of such an event; it fundamentally transforms a barotrauma-induced pneumothorax from a manageable incident into a protracted and costly medical ordeal.

To understand why, we must first grasp the delicate mechanics of the lungs and the havoc smoking wreaks upon them. Our lungs are miraculous structures, but they are fragile. The tiny air sacs, called alveoli, are where the vital exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide takes place. They are designed to be elastic, expanding and contracting with each breath. Barotrauma occurs during scuba diving when a diver ascends without properly exhaling. The air trapped in the lungs expands as the surrounding water pressure decreases. If this expanding air cannot escape, it can over-inflate and rupture the delicate alveolar walls. This tear allows air to leak into the space between the lung and the chest wall—the pleural space. This leaked air pushes on the lung, causing it to collapse, which is the definition of a pneumothorax.

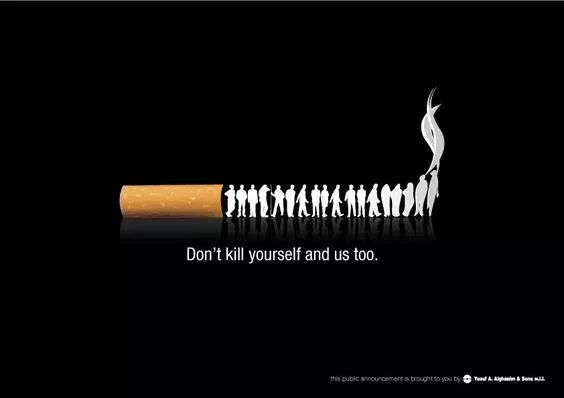

Now, introduce smoking into this picture. Cigarette smoke is a toxic cocktail of thousands of chemicals that directly assault the lung's architecture. It breaks down the very elastic fibers that give the lungs their resilience. This process, known as emphysematous change, turns healthy, springy lung tissue into brittle, baggy sacs with poor structural integrity. For a diver, this means their lungs are already primed for disaster. The alveolar walls are weaker and more prone to tearing under the stress of expanding air during ascent. Therefore, a smoker is inherently at a higher risk of suffering a barotrauma-induced pneumothorax simply because their lung tissue is compromised before they even take their first breath underwater.

However, the most significant financial and clinical impact of smoking is felt after the initial collapse occurs. Let's walk through the typical treatment pathways and see how a smoking history complicates each one.

For a small, uncomplicated pneumothorax in a otherwise healthy, non-smoking individual, the body often has a remarkable ability to heal itself. The leaked air is slowly reabsorbed, and the lung re-expands on its own. Treatment might involve simple observation in the hospital with supplemental oxygen, which can speed up the absorption process. This is a relatively low-cost approach, involving mostly room charges and monitoring. But for a smoker, this conservative management is far less likely to succeed. The chronic inflammation caused by smoking impairs the lung's natural healing mechanisms and the reabsorption of air. What might have been a 24-hour observation for a non-smoker can quickly turn into a 48 or 72-hour stay for a smoker, with no guarantee of success, thereby increasing hospitalization costs from the very beginning.

When simple observation isn't enough, the next line of treatment is needle aspiration or chest tube insertion. A small tube is inserted between the ribs into the pleural space to suction out the trapped air, allowing the lung to re-inflate. For a non-smoker with healthy lung tissue, once the leak has sealed itself—which it often does quickly—the tube can be removed, and the patient can be discharged. But here lies another critical juncture where smoking increases pneumothorax treatment costs. The same weakened, inflamed lung tissue that tore easily is now also slow to heal the tear. The air leak can persist for days, a condition known as a "persistent air leak." This means the chest tube must stay in place, requiring continued hospitalization, repeated X-rays, nursing care, and pain management. Each additional day with a chest tube in situ adds thousands of dollars to the hospital bill and significantly increases the risk of complications like infection (empyema), which would necessitate even more expensive antibiotics and interventions.

This is where we encounter one of the most significant long-term financial impacts of smoking on lung health. When a persistent air leak doesn't resolve after several days, or if the pneumothorax recurs—a common problem for smokers due to the formation of weak spots on the lung surface called blebs and bullae—the treatment escalates to major surgery. A video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is often required. In this procedure, a surgeon goes into the chest cavity to identify the leak, staple off the damaged portion of the lung, and often perform a pleurodesis. Pleurodesis is a process of creating inflammation between the lung and the chest wall, making them stick together and eliminating the space where air can accumulate, thereby preventing future collapses.

The cost difference between a simple chest tube and a VATS procedure with pleurodesis is staggering. The surgery itself involves surgeon's fees, anesthesiologist's fees, operating room time (which is exceptionally expensive), and sophisticated medical equipment. The recovery is longer, the hospital stay is extended, and the follow-up care is more intensive. A smoker is vastly more likely to require this surgical intervention than a non-smoker. Furthermore, smoking before surgery presents immense risks. It impairs circulation, reduces blood oxygen levels, and hampers wound healing, leading to a higher chance of post-operative complications like pneumonia or wound infections. Each complication is another layer of cost, another extension of the hospital stay, and another blow to the patient's recovery.

The financial ramifications extend far beyond the initial hospital discharge. A smoker recovering from a severe pneumothorax complicated by surgery faces a longer and more difficult rehabilitation period. They are more likely to experience prolonged pain, reduced lung function, and a longer time away from work, resulting in lost wages. The need for follow-up appointments, pulmonary function tests, and possibly even pulmonary rehabilitation programs adds to the cumulative economic burden. This creates a vicious cycle where the increased medical expenses from smoking-related complications can lead to financial stress, which in turn can make it harder to quit the habit that caused the problem in the first place.

The narrative is clear and unforgiving. The choice to smoke actively pre-invests in a future of heightened medical risk and exorbitant cost. For a diver, this is magnified. The combination of a high-risk activity and a habit that weakens the primary organ involved is a recipe for financial and physical disaster. The treatment protocol for smoking-related lung collapse is inherently more aggressive, more technologically dependent, and longer in duration. When we talk about the economic burden of preventable lung conditions, smoking-related complications from incidents like diving barotrauma are a prime example. The price tag isn't just on the hospital invoice; it's measured in lost time, prolonged suffering, and the long-term degradation of one's health.

The most powerful tool to avoid this steep cost is prevention. For divers who smoke, the most effective step is to quit smoking. The body begins to repair itself surprisingly quickly after quitting. While lung tissue may not fully regenerate, inflammation decreases, and the risk of complications from any future lung injury plummets. For any diver, smoker or not, proper diving education, controlled ascents, and never diving with a chest cold or respiratory infection are non-negotiable safety rules. But for the smoker, quitting is the single most important investment they can make—an investment that pays for itself not only by potentially saving them from a life-threatening incident but by shielding them from the overwhelming financial avalanche that follows when a simple collapsed lung becomes a complex medical crisis. The link between the habit and the hospital bill is direct, undeniable, and devastatingly expensive.